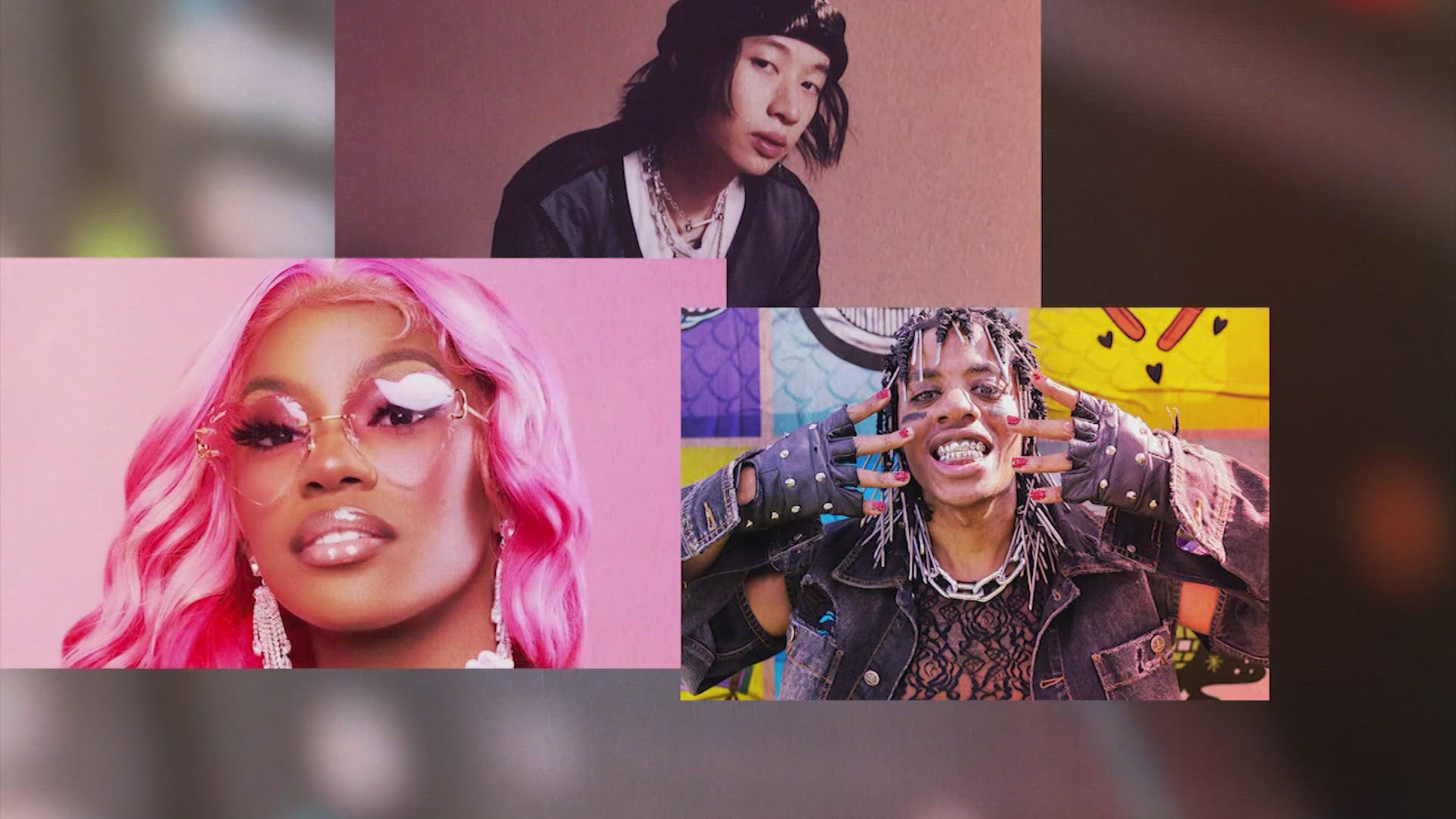

Juneteenth 1865-2024: A Legacy of Song

Many would argue the sounds of Africa influence every genre of music. This is the evolution of America's sound and its influence on culture.

Music is the tie that binds and the language that has flowed through and across cultures since the beginning of time.

Many would argue the rhythm, rhyme and the magic of a steady drum beat began in Africa. They’d also say the sounds of Africa influence every genre of music from folk and country to house, funk and rock. The heavy bass lines of hip-hop and the slashing of a heavy metal guitar are all influenced by African culture.

To truly understand the breadth of the impact of Africa on American music, we have to take it back to the Mother Land.

During the transatlantic slave trade, 55% of enslaved people were shipped to Brazil, 35% to the Caribbean Islands, and only 6% to the United States, according to historian Sam Collins. Brazilian sugar plantations drove the demand for slave labor much earlier than in the United States. The new nation would soon catch up naturally, as enslaved people started having babies in American colonies.

Tragically, children could be and often were sold away to other plantations and away from their mothers.

Even in slavery, music had the power to empower, celebrate and soothe. Lullabies cascaded from a mother’s lips to her children, and little ones played song games and made up songs they performed. There were even celebrations of cotton, cane and sugar, ahead of, and during harvest – a harvest that was brutal for enslaved people forced to work in the cruelest of conditions. Still, they worked and sang together in a rhythmic, but painful way that also served as a metronome for engineering and efficiency.

You would also hear singing fill the air in the slave quarters.

“Well, the only time they were in the quarters was at night because they were working from sun to sun,” said author and composer Naomi Mitchell Carrier. “And that was the time when there was an opportunity to express intimacy. And I'm sure there were love calls and expressions and, I mean, you know, music. Everybody has a voice. You can hum, you can whistle, you can sing, you can yell.”

There weren’t many instruments on the plantation. So, enslaved Africans would recreate the instruments they had while in their homeland. Because they didn’t have access to their instruments, many were recreated from memory.

"By the 1820s, it was very hard to find drums on farms and plantations across the U.S. South because they were used for rebellion," said University of Arizona Professor Tyina Steptoe, Ph.D.

Using only their voices to make music, enslaved people developed a song style and sound that would become the hallmark of Black music.

Birth and evolution of gospel ‘Swing low, sweet chariot'

The voices of the Prairie A&M University Concert Chorale were heard loud and bold one spring evening, singing an African American spiritual.

It’s an HBCU choral tradition that began in 1871 with the Fisk Jubilee Singers – six years after the Civil War.

Before choirs, spirituals were sung without instruments by enslaved people while they worked the fields, or for performance.

"They would have sung it, ‘Swing low, sweet chariot...' No music ‘..comin’ for to carry me home...’ (Knight Lab) Very a capella, very spontaneous," said Dr. Demetrius Robinson, choral director at Prairie View A&M University.

Prairie View sits on property that used to be a plantation, where slaves sang the very spirituals Robinson talks about. They are songs of joy, pain and hope for freedom. Eventually, field songs became church songs, and by the 1930s, a new genre was born – gospel.

"When we think about gospel as we know it, we have to think about people like Thomas Dorsey," Robinson said.

Dorsey became known as the father of gospel, having written "Precious Lord" at Pilgram Baptist Church in Chicago. He was pushing spirituals in a different direction. They became more up-tempo, sometimes blurring the lines between sacred and secular.

"Basic chord progressions, you might say it’s the blues,” Robinson said. “If you close your eyes, it might be Sunday morning.”

Gospel choirs exploded in popularity after Dorsey founded the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses. The music kept evolving, and gospel stars were born, like Mahalia Jackson, Mattie Moss Clark, the Reverand James Cleveland, and Edwin Hawkins, who turned the spiritual "Oh Happy Day" upside down.

From capture to bondage and freedom, spirituals have been woven into the fabric of African American lives.

"So every musical style we know of today, you can trace it back to the spirituals,” Robinson said. “We are talking about gospel, ragtime, jazz, blues all these different things you can link back to the spiritual.”

Emancipation Day Let freedom ring

"Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves"

― Abraham Lincoln, Complete Works - Volume XII)

By 1863 freedom rang, but not for all, despite President Abraham Lincoln issuing the Emancipation Proclamation declaring all persons held as slaves be freed.

So many people relate to the Emancipation Proclamation, which President Abraham Lincoln, signed in September 1862 to go into effect January 1, 1863. On January 1, there was a battle of Galveston where the Confederate Army took back control of the island, delaying enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. Because the Confederate army regained control of the port city of Galveston, that delayed enforcement for two and a half years.

June 19, 1865, U.S. General Gordon Granger and troops arrived in Galveston to issue and enforce General Order No. 3 liberating all enslaved people.

The Union soldiers, many of them being United States colored troops, were to move throughout the island,” said historian Sam Collins. “And one of the places being Reedy Chapel that it is believed through oral histories and stories that the notice was posted on the door, because the church, of course, is central to the African American community and part of the foundation of faith.”

Reedy Chapel Church is a place of worship that's played witness to history.

“This church is almost as old as Galveston itself,” said Sharon Batiste Gillins - Genealogist and Reedy Chapel Church Member

Reedy Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church known as the mother church of Texas has withstood the test of time.

“Everything that Galveston went through historically, this church went through. We were here when the 1900 storm came, when the 1885 Great Fire of Galveston came when emancipation came in 1865, this church was already in existence,” Gillins said.

She said Reedy Chapel was part of the Methodist Episcopal Church South, which was a predominantly white congregation.

“At some point in 1848, they purchased a lot for the benefit of their enslaved people,” Gillins said. “That meant that the enslaved people who had up to that point been worshiping with the white congregation now moved their worship to this spot and worshiped outdoors until they could build a church edifice for themselves.”

The formation of the church likely increased the music, the drumming, and the preaching and their call in worship, Gillins said.

This gave hope to an oppressed people ahead of Emancipation Day on June 19, 1865.

“Juneteenth is my 4th of July. It is the point in time which my ancestors were then recognized as people before June 19, 1865, Gillins said. “I cannot research my family as people. I had to research my family as property because that's what they were. They were not listed in vital records. They could not marry—legally marry—because they were property.”

Enslaved people were informed of their newfound rights by mostly Black soldiers at Reedy Chapel. It became one of the most important locations for the announcement of emancipation.

“General Gordon Granger and the United States colored troops and Union troops arrived here in Galveston not to announce emancipation, but to enforce emancipation,” Gillins said. “And this church would have been the closest church for African descendants to the port of arrival.”

With newfound freedom came a flourish of activity in the church and the acquisition of materials and instruments, including the organ above the altar.

“It is a beautiful organ. It's just visually stunning. It’s a historic 1872, Hooke and Hastings,” Gillns said. “Pipe organ and pipe is only one of two in the nation, and the other one is in the Smithsonian. So it has quite a bit of significance here, and it definitely creates a beautiful backdrop for the pulpit and the and the altar here.”

The music pushed out of the age-old pipes, up toward the heavens, and into the chapel. The sounds are captivating, moving people in the pews during Sunday service. Together they sing and give gratitude for their faith, their freedom and most of all the church.

“So that's our history. That's our heritage,” Gillins said. “That's not only Reedy's history. It's Galveston's history. It's Texas history, and it's United States history.”

The Black National Anthem "Lift every voice"

“Lift Every Voice and Sing”, also known as “The Negro National Anthem” and “The Black National Anthem,” was first written as a poem by James Weldon Johnson an educator, attorney, and diplomat. Johnson's brother John Rosamond Johnson, a songwriter and singer, composed the music to accompany the lyrics.

In 1900, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was first performed in public by 500 black schoolchildren to honor President Abraham Lincoln's birthday. In 1919, the NAACP proclaimed “Lift Every Voice and Sing” as the Negro National Anthem, 12 years before "The Star-Spangled Banner" was adopted as the National Anthem. The song was widely used during the Civil Rights Movement by demonstrators who sang and walked arm-in-arm while marching for equal rights.

"Lift Every Voice and Sing" has been performed to mark historic milestones including the 1990 release of Nelson Mandela from prison, the 2009 inauguration of President Barack Obama, and the 60th Anniversary of the March on Washington for Civil Rights in 2023. In the last few years, it's become a part of the Super Bowl opening ceremonies.

Young, gifted, and Black.

From college concert halls to intimate venues and grand theaters like the Wortham Center and beyond, classically trained musicians and singers have a bright future ahead thanks to the greats of the past.

Marian Anderson sang on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1939 and became the first Black soloist at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

The acclaimed soprano Leontyne Price hit the Met stage in 1961. George Shirley became the first Black tenor to sing leading roles at the Met. Just a few of the names who blazed a trail for a growing number of African American opera singers today.

That new generation includes tenor Lawrence Brownlee, and Houston-based soprano Nicole Heaston. Their journey to classical music started in the church.

I grew up in church,” Brownlee said. “I didn't know what opera was about until I was exposed to it."

“When I started winning competitions in high school, I could dress up and sing and communicate in a different language,” Heaston said.

She could sing in a different language and a very different technique. Opera singers belt out songs without microphones.

"We use muscles in a different way, using our whole body to make the sound,” Heaston said.

Now, Heaston and Brownlee mentor up-and-coming opera singers like Cory McGee and Renee Richardson.

Ragtime "a uniquely African American musical style"

“I love playing ragtime because it's really a uniquely African American musical style,” said pianist Sasha. “I really wanted to play a piece by an African American composer, Artie Matthews because I just feel so connected to my ancestry and my heritage when I get to play this music.”

University of Arizona professor Dr. Tyina Steptoe said ragtime developed in different parts of the country around the late 1800s into the early 1900s.

“It's a very important precursor to jazz because ragtime, ragtime is a very syncopated dance music that for a long time had kind of a seedy reputation because it was sometimes played in the same places where maybe gambling and prostitution and drinking went on,” Steptoe said.

She said ragtime became a craze by 1910 because people heard this music and they were familiar the instruments, but they had never heard the instruments played in such a way. Steptoe said ragtime may have been the first version of Black music in the United States that crossed over to become mainstream. In the 1920s, jazz replaced ragtime in its popularity.

Jazz From blues to jazz

By the turn of the 20th Century, some New Orleans jazz musicians were innovating what later became jazz, according to Steptoe. They were still calling it blues as there was no distinction between the two genres.

Zydeco Rich in culture and sound

Zydeco music is as rich in culture as it is in sound.

“Zydeco music is a happy festive music,” musician Step Ridueau said. “It's the type of music that makes you move. It's paired with a dance.

Rideau is a Southwest Louisiana transplant, one of the genre's most popular musicians, and a master of the accordion. The accordion is accompanied by a more modest instrument -- the washboard.

The combined sounds filled rural Louisiana French-speaking farm families' homes dating back to the early 20th Century. Folks knew it back then as la-la music.

Generations of southwest Louisiana Creole families of color brought la-la with them to Houston after the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and established French Town.

At the time French Town was created, Houston had a really booming economy,” Steptoe said.

They found work with the Southern Pacific Railroad. Together, they established their enclave in Houston's Fifth Ward -- with their own traditions, within just a few square miles. They built shotgun houses, established our Mother of Mercy Catholic Church, and patronized businesses, like the Deluxe Theater.

Steptoe, a Houston native, writes about music, history, and the Black experience. She says French Town and the Fifth Ward are where la-la evolved into zydeco.

“The sounds changed a lot with that migration into Houston,” Steptoe said. “You see people swapping out instruments (and) taking on new ones.”

With new instruments and sounds, came a new name for the music. Zydeco music flourished and grew in popularity. By the 1980s the French Town community had faded.

The construction of the interstate system, I think, divides a lot of Black communities nationwide, but right here in Houston, you especially see the effects of that in Fifth Ward where I-10 cuts through parts of Fifth Ward (and) 59 cuts through another part,” Steptoe said.

While French Town in Fifth Ward may be no more, the music is still loved and celebrated.

Rock and Roll "My daddy rocks me with the steady roll"

The term Rock and Roll comes out of Black vernacular.

As early as the 1930s, there were songs that we're talking about rocking and rolling, and some of them came from Black people who sang the blues, according to Steptoe.

“Lots of references to ‘my daddy rocks me with the steady roll,’ right?” Steptoes said. “And then after World War II is when the style of rock and roll started to take shape. But at the time, it was being called rhythm and blues.

The El Dorado Ballroom Black history in Third Ward

Whether it was rock and roll, big band swing, blues or jazz, African Americans sought their own elevated spaces and dance halls to host parties and performances. They desired a venue where they were the guests, and treated with dignity, not just entertainers playing to white-only audiences during the Jim Crow era of segregation.

The Eldorado Ballroom in Houston's historic Third Ward provided that upscale place for Black Houstonians starting in 1939.

This was the Savoy Ballroom and more in our region of the country. It saw all sorts of award-winning premiere acts.

“Ray Charles performing, Duke, Count Baisse, Great Conrad Johnson, ‘Dowling Street Song,’” music historian and writer Roger Wood listed. “In the song, (it) mentions Eldorado. It represents achievement and status among patrons but also musicians. People like Iah Smalley, Ed Golding, Arnett Cobb, Milton Larkin … these were some of the band leaders that were there. Bands were typically wearing tuxes and stuff. It was a prestigious venue.”

A young Jewel Brown cut her teeth at the Eldorado Ballroom before performing with marquis acts like the legenday Louis Armstrong.

The Eldorado shuttered briefly but reopened for a few years in the 70s before permanently closing. Unused and abandoned, the building fell into disarray but still had fans, including a white fan of Black music who as a young boy would stand outside and listen to the jazz musicians.

He bought the Eldorado in the early 80s before gifting it in 1999 to Project Row Houses, a group of Houston artists dedicated to protecting and preserving the rich history of Houston's Third Ward.

“Once Project Row Houses acquired it, there were a series of events, especially in those first few years,” Wood said. “November 2003, that would have been the 100th anniversary of the birth of Houstonian Don Robey who went on to found Duke and Peacock Records.

“It's the first time that there's a Black person in charge of what's going on, and he predates so many of the Black entrepreneurs who are going to use music as a base of their economic empires,” Steptoe said. “You know, without Don Robey, there's not even a Berry Gordy in Detroit to inspire by what he's seeing going on in Houston. And Berry Gordy has said before in interviews that he was inspired by Don Robey and Duke Peacock.”

Under new direction and with the generous support of Houston's philanthropic community to the tune of $10 million, the Eldorado Ballroom underwent a massive renovation and remodeling.

RELATED: 'It's about to glow up' | Houston's Eldorado Ballroom restoration project underway

In spring 2023 it reopened its doors as a special events venue.

“So many American cities look the same, but when you find something this distinctive, that's rooted in that place historically it isn't just physically there,” Wood said. “It's of that place, you know, that's a different kind of thing. It can meet a need that goes far beyond music history. It's a place where people can connect, connect with the neighborhood, connect with the city and connect with our history."

Disco and funk Post-Civil Rights music

A new decade ushered in an old sound that took Black music back to its roots.

“I think you could hear that in some of the funk music of the late sixties, early seventies, where people start producing these nine-minute songs, right?” said KTSU 90.9 General Manager Ernest Walker. “I think Parliament maybe might have a 15-minute song, and a lot of that is trying to intentionally tap into the music of our ancestors.”

“That emphasis on rhythm is so key to late sixties, early seventies music,” Steptoe said. “People were being very intentional about these heavy, hard rhythms.”

Funk music is a sound that coincides with disco.

"Jim Crow told people where they were allowed to exist. You could not go here if your skin is this color,” Steptoe said. “You can't sit in this part of the bus. But then, I think, that there's a reason that disco is the post-Civil Rights music."

She said she thinks the dance music was liberating with an uplifting message.

“And I think if you look at the people who were the most popular disco artists, these are all people of color. They are diverse women,’ Steptoe said. “And you also have a lot of influence of LGBTQ musicians in disco. And I think that that's where some of the liberating aspects of disco come from. It's just maybe not happening in a march, it's happening on a dance floor."

Around 1980, R&B and funk artists started rapping in their songs. A rap verse on a song became a standard around that time.

Rap and the H-Town sound Unapologetically Houston

Around that same time, Houston rap artists were coming into their own, which gave birth to the H-Town Sound and a new generation of music producers, artists and musicians who were unapologetically Houston in their music and style.

Houston has produced some of the industry’s biggest stars, including Willie D of the Geto Boys, Lil’ KeKe, and Bun B a.k.a. The Trill O.G.

All three represent Houston and the Houston sound hard. They said the city had to stand out from the start when it came to music.

“Before we put Geto Boys out, people really still thought we were riding around on horses and wagons out here,” explained Willie D. “You know, people in Houston were just buying records, and we were very supportive of everybody. As long as it was hot, we were owning it, and at some point, we were like, 'we have something to say, too.' So, we started chronicling our experiences, our Southern experiences in particular. We wasn't familiar with subways, we wasn't familiar with gangs and things like that. We didn't do that. So, we talked about the things that we did."

Neighborhoods and life in the streets drove the lyrics. It’s an entire culture with its own language. It is also a language that speaks to fans and music executives.

There’s mutual respect and admiration, with plenty to go around, for those no longer here like Bushwick Bill, Pimp C, Fat Pat and the legendary DJ Screw who birthed a genre within rap: Chopped and Screwed. All these artists influenced other heavy hitters.

While they’re admittedly no longer the youngest in the Houston rap game, they remain relevant. All of these artists influenced other heavy hitters. Collectively they've cranked out so many classics. Together, they'll just keep swangin’ and bangin’.

Rappers Paul Wall and Mike Jones built their brands on the foundation already laid by pioneers of the sound.

Now, a new breed of H-Town stars is on the rise.

KenTheMan is one of those stars. She started rapping for fun with her friends in north Houston and isn’t planning on living elsewhere. She has more than 100 million streams over several platforms. As for her Houston style and flow,“ I can't really put my finger on it, but I just feel like Houston," KenTheMan said. "We're known for, like, freestyle out in the car. Like we are just chill. We are just freestyle."

That Mexican OT is another artist making some noise and climbing the charts. His hit song "Johnny Dang” debuted in the Billboard’s top 100 in 2023. Then you have X factor star Josh Levi, whose song “Birthday Dance” went viral on social media. His success on the hit show earned him a record deal.

Other new Houston artists gaining speed include singer Keshi?, rap artists Monaleo and Teezo Tchdwon. Taking the country world by storm is North Houston’s Julia Cole. She said her volleyball team discovered her talent when she sang in the locker room randomly. “My volleyball coach was like, 'Why don't you send a video in to the Texans?' So, then I started doing the anthem for the Texans, Astros, Houston Dynamo, Houston Rodeo, Houston Livestock Show and Radio,” Cole said.

The CMT 2022 next women of country star, instantly fell in love with performing and moved to Nashville but didn’t forget her Texas roots.

Modern music with a message A call to action

Music has remained a call to action for African American artists like Tobe Nwigwe and his song 'I Need You To,' which calls for justice in the death of Breonna Taylor.

Black musicians have composed, conceptualized, played, and sung just about every genre for every audience, and on some occasions they have combined all these sounds and talents to create something special.

Singer, songwriter and musician Gabe Baker has a special touch with the cello, an instrument and sound that's made him a standout then and now.

Baker attended Rice University where he studied environmental engineering and was the captain of the football team. He made three bowl appearances and one conference championship. Back then, Baker played the cello more as a hobby, dabbling in the campus orchestra and taking lessons when he could find the time.

“For one semester, I took lessons from a grad student, a cellist who was a great student here at the Shepherd School all up until I broke my hand during football spring practices,” Baker said. “To me, it was like the colliding of the two worlds. I just remember I was like, 'hey man, I can't take lessons anymore.'"

Years later, his hand was more than fine. Now he plays and tours with the international Christian pop duo sensation For King and Country. They travel the world playing for packed audiences from Australia to the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

“I get so much satisfaction from doing music in general, and then also being able to branch out to different expressions of instrumentally, even songwriting or collaboration lines, Baker said. “Not feeling like I have to be in a certain box or a certain aspect of music gives me a lot of satisfaction.”

It gives him a lot of freedom to be himself and create, while remembering his roots.

“I'm definitely a homage to so many great creatives that have come before me,” Baker said.

Like those who came before him pushing musical boundaries, Baker could very well define the next genre and sound.

Emancipation Park and Juneteenth The heart of Third Ward

Music festivals bring artists to the people and in the case of Juneteenth, to the heart of Third Ward and Emancipation Park.

It's there where Houstonians mark Juneteenth, the park that in 1872, four former enslaved men purchased for African Americans to have a place to celebrate the freedom holiday.

Now, there are several celebrations, including an annual music festival.

“I think you could have a debate on what's more important to Juneteenth, the barbecue or the music,” Steptoe said. “When I think about it, I think about who are the artists who are going to be performing at a Juneteenth festival. But in my research, I have found going way back to the early 20th century, I have evidence of Juneteenth celebrations being a place where the organizers spotlighted the local music of what was going on.”

Music is a big part of Black culture. It’s something that has been passed down from the ancestors.

“If you look at something like Juneteenth and Emancipation Park and who's headlining is always a big deal and a big draw to it. It also shows just the significance of music to black history, and especially the history of emancipation itself," Steptoe said.