One pill: Fighting fentanyl

Fentanyl is the deadliest drug threat in the U.S. Its victims are getting younger. Many don't know they're taking it. This is what their families want you to know.

It is considered the deadliest drug threat our country has ever seen. Think about that. Not over the past 10 years; not the past 20 --ever. Illicit fentanyl is cheap, potent and immensely profitable. More problematic, it’s often deceptive.

Drug traffickers in makeshift labs often mix fentanyl into fake prescription pills, with little regard for precision or quality control. Many who buy them on social media don’t know what they’re getting. They don’t know they are poisoned. They don’t know the odds of not waking up are worse than a coin flip.

Illicit fentanyl is killing in record numbers and its victims are getting younger. As law enforcement and the government work to combat the spread of deadly fentanyl, many parents are refusing to sit on the sidelines. They couldn’t save their own children, so they’re trying to save others. For them, fighting fentanyl means arming others with information, awareness and advocacy. Their battle cry: One pill can kill.

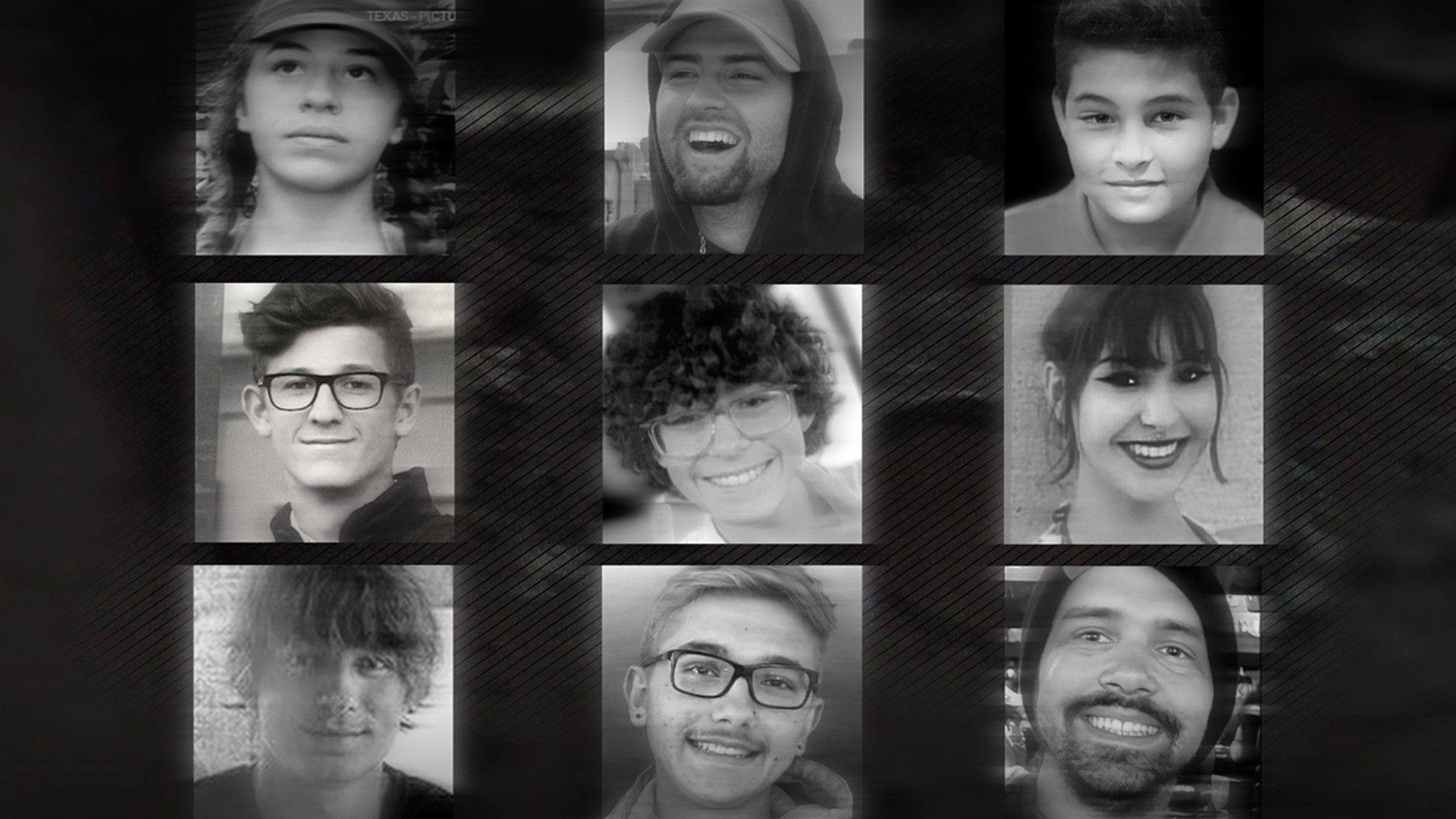

Josh's Story "Just your everyday normal kid."

Growing up, Joshua Gillihan loved to ride dirt bikes, ski and spend time on the water in the family boat. He played Little League and took up Taekwondo.

His family went on camping trips and vacations to Walt Disney World. Josh grew up in a loving home in Cypress with loving parents who called him their "miracle child," born after five in vitro fertilizations.

“Just your everyday normal kid,” said his mother, Kim Gillihan.

Like many kids, the curly-haired 14-year-old ran into some bumps along the way. In seventh grade, Kim and her husband Steve found Josh with marijuana for the first time. Concerned, they talked to their son about the dangers of drugs and kept a closer eye on their boy. After it happened again, they grounded him and took his phone away. They got Josh counseling and even set up cameras to see who was coming over to the house.

As Josh began his freshman year at Bridgeland High School in Cy-Fair ISD, mom and dad hoped it all was behind them. They hoped it was just a phase.

“Everything was going really good,” Kim said. “The first week of school came and he had a great first week at school and I said, ‘I think we’ve turned the corner.’”

It was Friday and Kim was heading out of town the next day for a business trip. She made a quick run to the store so Josh could pack his lunches, not forgetting the Jell-O pudding he loved. On the way home, Kim picked up burgers and they ate dinner on the kitchen island. Josh was excited about a girl he met and was thinking of asking her to homecoming.

“’Mom, where do we get a mum?’” Kim recalled him asking.

She chuckled and told her son not to worry. They would figure it out.

“Josh had the best first week of school we could have ever imagined, you know, just everything went so well,” she said.

The next morning, Kim rushed around with last-minute packing and put her luggage on the front steps.

“I thought, ‘I got to go and give him a hug goodbye. He’ll be so upset if I don’t,’” she said.

Kim went upstairs and called Josh’s name. He didn’t answer. She called his name again, and again no answer. Kim walked into his bedroom and leaned over.

“And then I just reached down to kind of like, you know, jostle him, and the minute I touched him I knew he was gone,” she said. “He was ice cold.”

Kim screamed—a piercing shriek captured on the in-home camera the couple installed. It was followed by frantic calls to 911 and a close friend. Police and paramedics rushed to the home, only to confirm the Gillihans' only child, their miracle child, was dead.

“Josh thought he had taken an Oxy(Contin) or Percocet, and it was pure fentanyl,” Kim said. “He would never have taken that pill if he had known what was in it. And that’s the point--you don’t know. Nobody knows.”

Deadly Spike Rise in fentanyl deaths

Deaths involving fentanyl have spiked dramatically in the Houston area, according to a KHOU 11 analysis of medical examiner records. From 2018 to 2022, there was a 467% increase in Harris County, a 338% increase in Galveston County, and a 325% increase in Montgomery County. The Fort Bend County Medical Examiner's Office opened in late 2019 and saw a 158% increase in fentanyl-related deaths from 2020 to 2022.

A closer examination of records reveals a more alarming spike in two counties for victims ages 21 and younger. In Montgomery County from 2018 to 2022, there was an 800% increase in fentanyl-related deaths. In Harris County, there was a 933% increase.

“Fentanyl is the deadliest drug on the market today,” said Robert Kennedy, Assistant Special Agent in Charge of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration office in Laredo. “Fifty times more powerful than heroin, 100 times more powerful than morphine.”

The synthetic opioid binds to receptors in the brain to block out pain. It produces an incredible high and is highly addictive. A key to a drug trafficker’s bottom line.

“If they get you hooked and you live, you’ll be back, if you don’t live, they’ll find another client,” Kennedy said.

It can only take two milligrams of illicit fentanyl to be lethal—an amount so tiny it would fit on the tip of a pencil. A typical salt packet from a fast-food restaurant contains about 750 milligrams. Kennedy said drug traffickers will make fentanyl-laced pills to look identical to real prescription medications including OxyContin, Percocet, Adderall and Xanax.

“When we send our pills to the lab, six out of 10 pills are coming back as lethal dosage(s) of fentanyl, that's 60% of our pills,” Kennedy said.

The odds are worse than playing Russian roulette.

“You're playing with your life and there's a 60% chance that you'll end up losing,” Kennedy said.

At the Houston Fire Department, paramedics see the crisis firsthand.

“All over the city, it’s daily,” said Captain Michael Prigmore, an EMS supervisor with nearly two decades of experience. “It’s the scariest thing I’ve run across in my 19 years.”

With any emergency, seconds matter for first responders. With fentanyl, Prigmore said it’s even more of a race against the clock.

“It’s extremely potent and it works fast,” Prigmore said. “You’ve got about five to seven minutes before the brain stops working, and so if we get there in that amount of time before they actually stop breathing completely, we can reverse it.”

Prigmore regularly finds himself restocking ambulances with the naloxone nasal spray Narcan, which temporarily blocks the effects of synthetic opioids like fentanyl and restores breathing.

Too often, 911 calls end up like 14-year-old Joshua, the miracle child of Kim and Steve, whose body was wheeled out of their Cypress home on a gurney. The haunting image was captured on video from a security camera focused on the front door. The parents decided to make it public, along with the moment Kim found her son lifeless in bed.

“I feel like that if I could have shown my son something like that, maybe that would have gotten through to him,” Kim said. “We were like, ‘We have this footage, and we need to figure out how to use it so that we can wake people up.’”

Kim shows the videos at awareness events, like a recent gathering at the Cypress VFW Post 8905. Her wake-up call is working by the looks of the young faces who came to hear her, and other grieving mothers speak.

“I saw people that were really engaged … I felt like their minds were blown,” Kim said. “I think that it takes something like that to get through to people sometimes, to show the reality of it. One pill will kill.”

Fentanyl Flowing into America "It's a game of cat and mouse"

The pill that killed Josh more than likely came across the U.S. southern border.

“Mexico is the source of the vast majority of the methamphetamine, heroin and illicit fentanyl seized in the United States,” according to the U.S. State Department’s latest International Narcotics Control Strategy report.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration identified the Sinaloa and Jalisco (CJNG) cartels as the primary manufacturers, using precursor chemicals shipped from China.

Once cartels mix fentanyl powder with drugs such as heroin or press it into counterfeit pills, delivering it north becomes a game of catch me if you can with border security officials.

“It's very challenging to inspect the amount of traffic that comes through here,” said Alberto Perez, the border security coordinator for the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Laredo Field Office.

Perez said roughly 5,000 to 6,000 vehicles cross the Juárez–Lincoln International Bridge every day. It’s just one of five border crossings in Laredo and one of 48 along the entire U.S.-Mexico border. With so much traffic, fentanyl drug smugglers are keenly aware it’s a numbers game in which CBP officers simply cannot inspect it all.

“It's a game of cat and mouse or finding that needle in the haystack,” Perez said.

To find the drugs, federal officers rely on a wide-ranging toolbox from high-tech gadgetry to human gut instinct. It all begins with the initial “meet and greet” when CBP officers have their first contact with the traveling public.

“They're looking for those signs of deception, so they're trying to key in on those little cues that are going to raise those red flags that's going to cue the officer to say, ‘Hey, I need to look at this vehicle a little bit more closely,’” Perez said.

One such vehicle was a Volkswagen Beetle that CBP officers couldn’t open the front trunk. It was sent to a secondary inspection station where the entire car was given a more thorough exam.

A fiber optic scope was shoved into the gas tank to search for anything that shouldn’t be there. It’s just one piece of available technology. There are giant X-ray machines to run vehicles through, as well as density meters that can identify drugs behind a car’s outer wall, much like a stud finder. Add to that, low-tech mirrors to check a vehicle’s underside, and high-powered noses from trained K-9 officers.

Fentanyl smugglers will try and hide their illicit goods just about anywhere.

“We’ve seen tires; we’ve seen bumpers; seen quarter panels, car batteries, car seats, car floors, car roofs. So basically anything, anywhere, any crevice a vehicle has, they’ll try to put in there,” said U.S. Customs and Border Protection Officer Angel Chavez.

Unlike smuggling other drugs, less is more with fentanyl.

“What makes it different is really, you can smuggle a small amount of fentanyl into the United States and you're going to be able to make more money off of that than you would cocaine, or you know, heroin,” Perez said.

That makes officers’ jobs more difficult and more time-consuming. It took about 10 minutes for officers to open the jammed front trunk of the Volkswagen. Turned out, there was nothing inside, but if there was, they would do a field test on the substance in an on-site garage.

“We don’t know what we have until we find out what we have,” Chavez said.

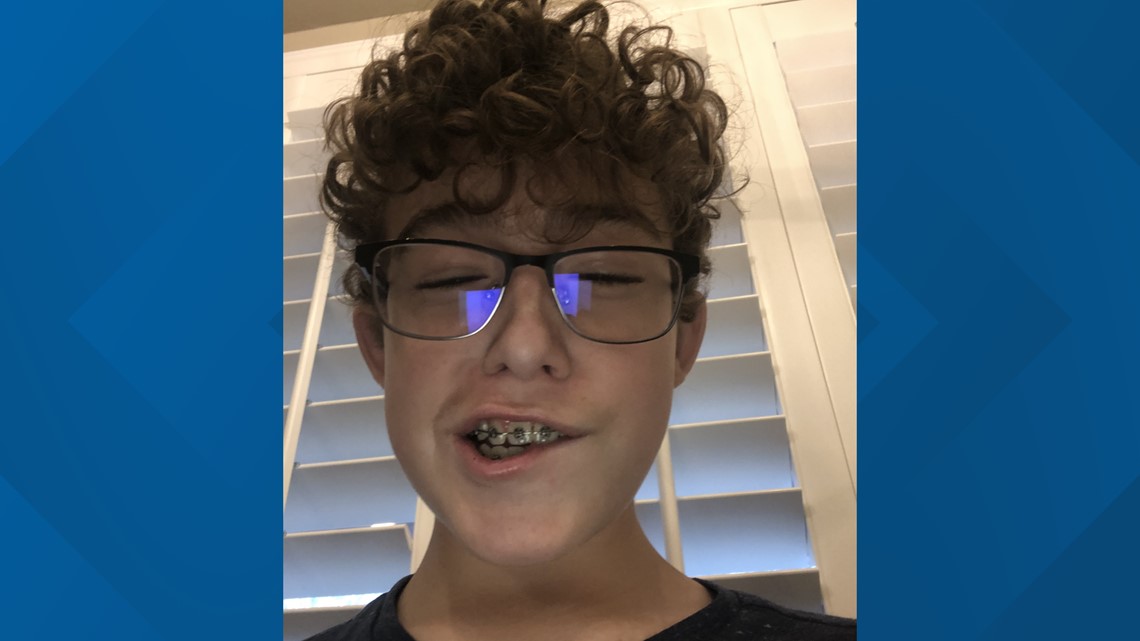

Fentanyl seizures nationwide by CBP have tripled over the past three fiscal years. In fiscal year 2020, the agency seized 4,800 pounds. In fiscal year 2021, that increased to 11,200 pounds and jumped again to 14,700 pounds in fiscal year 2022. So far this fiscal year, the agency has seized 13,900 pounds, on pace to break last year’s record with months still go.

Every day brings more cars and trucks to America. Thousands more on the Juárez–Lincoln International Bridge in Laredo alone. It’s another day of catch me if you can.

“It’s impossible to do 100%,” Perez said. “It’s a numbers game. I think they’re trying to exploit that you have all this traffic, and you’re able to exploit that in order to smuggle these narcotics into the U.S.”

The fentanyl that does make it through, is killing in record numbers. During his One Pill Kills fentanyl summit in April, Gov. Greg Abbott said more than 2,000 Texans died from fentanyl last year.

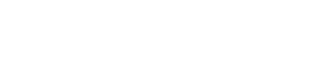

The Faces of Fentanyl Never say, "Not my child"

One Houston filmmaker is making sure the fentanyl death toll is not just about numbers.

“I’m a storyteller,” said Glen Muse, founder of Texas Pictures. “Everybody grows when a person shares a story.”

Last fall, when the DEA asked Muse to tell the stories of those who lost loved ones to the fentanyl crisis, they shared their hearts and bared their souls.

“It’s like the worst thing that we’ll ever go through,” said mother Lisa Wheeler.

“It was one pill,” said mother Andrea McCutcheon.

“That one pill cost him his life,” added mother Stephanie Hellstern.

Over a simple black background, parents look straight into Muse’s camera to share their deepest, darkest, most personal moments. Brandi Melo found out her 13-year-old son Kaysen Villarreal died when friends he had stayed the night with posted a picture of his body on Snapchat.

“I prayed the whole way over to his friend’s apartment and when we got there the cops were already there,” Melo told Muse through tears. “And I’m going up and I’m like, ‘Where’s Kaysen? Where’s Kaysen?’ And they come up and bombard me and are like, ‘He’s gone. He’s gone.” And I’m like, ‘Where?’ And they said, ‘He’s laying on the living room floor.’”

At his home office, Muse painstakingly edits the stories himself.

“I probably cry a little bit with every story when I’m working on it,” he said. “We really connect with them.”

That connection and personalization triggered a huge response. When Muse put their stories online, they took off. The Texas Pictures Fentanyl Poisoning Series has more than 7.8 million YouTube views and is growing every day. Muse said he was blown away by the online reception and attributes the interest to the topic itself.

“So many of the comments that we’ve seen are from people who are saying ‘me too,’” Muse said. “They’re saying, ‘I lost a son or daughter. I lost a friend. I lost a brother to the same thing.’”

Now, families are reaching out to Muse and Texas Pictures on their own to share their stories. What initially began as a collection of 16 tributes to those who died from fentanyl poisoning, has now grown to more than 40 online. Half of those featured are ages 21 and younger.

There are parents whose children suffered from long-term addiction, like 19-year-old Jackson Schiller.

“We tried everything that we knew and we were told might work, but there was never anything as powerful as the drive to receive the drug of choice and to use,” said Dwayne Schiller, Jackson’s father.

“When the rehab driver went to pick him up, unfortunately, he was deceased in the hotel room,” said Lynn Schiller, Jackson’s mother.

The series also includes many parents whose loved ones were just experimenting with pills like 17-year-old Danica Kaprosy.

“Kids, instead of learning from their mistakes or experiences, you know, and moving on with their life, they’re dying,” her mother Veronica Kaprosy said. “My soul died. I am dead. I’m dead on the inside.”

When asked why they shared their most personal, private and painful moments in life for all to see, the answer was clear.

“To save another child; I couldn’t save mine, so I’m trying to save yours,” Kaprosy said.

“I don’t want anybody else to feel what we have felt,” Lynn Schiller said. “It’s simply our goal to save the next kid.”

That advocacy and awareness from many who’ve sat in front of the camera also came with a resounding message—it can happen to anybody.

“Everybody thinks ‘not my kid, it’s not going to happen to my kid,’” said Kristina Villagrana, mother of 29-year-old Kyle Hinkle.

“I’ll admit maybe I was also thinking, ‘OK not my family. Not me. Not anybody I know,’” said Stephanie Hellstern, mother of 16-year-old Kyle Sexton.

“Don’t ever say that -- ‘Not my child; not my child.’ -- because I’m sitting here today. I never thought my honor roll student, football player, athlete, would not be here today, never thought,” said Janel Rodriguez, mother of 16-year-old Noah.

They are pleas that hit home—raw and real—captured through the lens of a storyteller, moving the needle in the fight against fentanyl.

“It has to have touched some lives,” Muse said. “Somewhere there has got to be one person who’s alive because they saw what we did.”

From Street Corner to Social Media Dealers are just a click away

Where are kids getting their hands on these pills? According to veteran narcotics detectives, unlike the old days when drug deals mostly went down on the street corners, hundreds of dealers are now just a click away on just about any social media app.

“I mean the phones are everything,” said Justin, an undercover detective for the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Department who requested his last name not be used. “Their phone is gold to us, because that’s where all the information is going to be that leads us to where they got the drugs that made them die.”

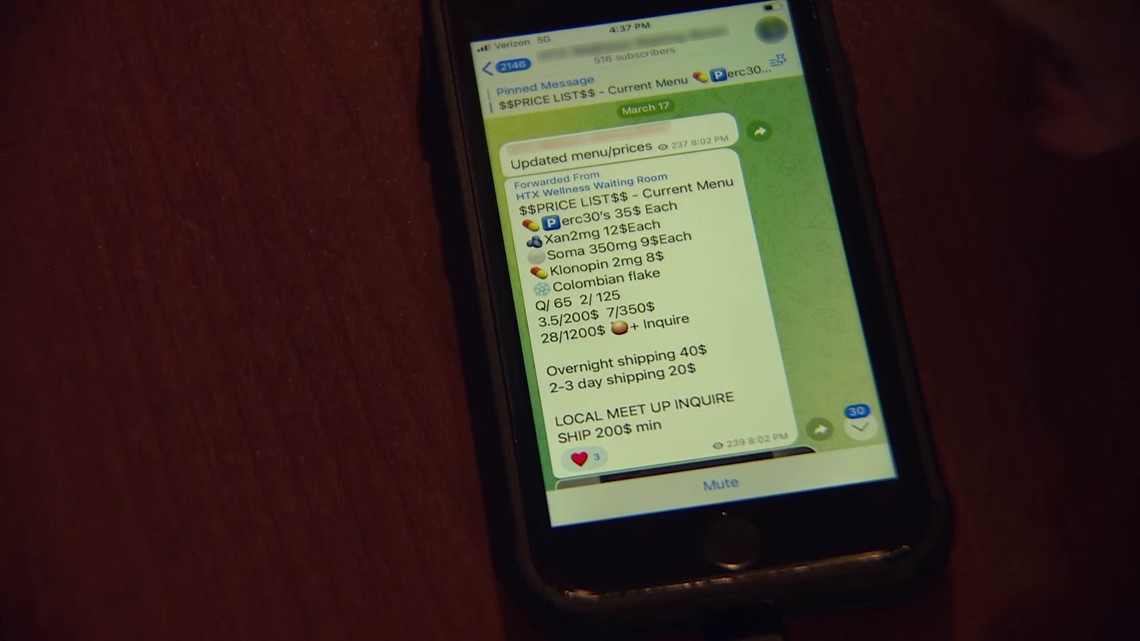

Justin and other investigators are assigned to MOCONET, the Montgomery County Narcotics Enforcement Team. They work death investigations and proactive drug cases, using social media to get leads and gather evidence. Justin scrolled through screenshots of social media posts that showed a smorgasbord of drugs for sale. They often include pressed counterfeit pills that could contain fentanyl.

“They'll post something onto Snapchat and it'll say, ‘I've got blues, which could be Percocets. I've got Xanax,’” he said.

Justin said buying drugs nowadays is as easy as ordering a pizza.

“We have some of these guys, just kind of like a fast-food restaurant, they put their menu up,” he said. “’Hey, I’ve got this, this and this, just hit me up, I’ll get you whatever you need,’ and they do that all day long, 365.”

Using AI to Fight the Crisis "There's too much drug selling" going" on.”

It would seem impossible to track all of it, all day, every day. But one company in San Diego is trying to do just that. S-3 Research was formed in 2017 when a team led by Tim Mackey, Ph.D., was named as a finalist in the Opioid Code-a-Thon. It was a competition organized by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to develop data-driven solutions to combat the opioid epidemic. From there, the company received a startup award from the National Institutes of Health and began tracking online drug sales.

“We're looking at millions of posts and millions of types of data from different platforms. One platform’s data looks different than another platform’s data,” Mackey said. “And so, the problem is there's too much data, to be honest. There's too much drug selling going on.”

S-3 research uses machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence, to flag thousands of drug-related keywords on various social media platforms and the dark web.

“We collect that data. We use our machine learning to classify that data for those people who are explicitly selling, and then we visualize it so that different clients can use that information to take action,” Mackey said.

His company’s clients come from both the private and public sectors. They include Snapchat and the Colorado Attorney General’s Office, which issued a 182-page report in March about social media, fentanyl and illegal drug sales.

S-3 Research identifies tens of thousands of illicit drug sales. The company’s data visualization dashboard can rank them by who is selling the most, map them to identify drug-selling clusters and sort them by individual platform. The posts range from the out-in-the-open, nothing-to-hide variety, to more cryptic advertising using emojis and QR codes. It all gets archived so there’s a record of what went on.

“It’s literally a restaurant menu of drugs,” said Lead Threat Analyst Matthew Nali.

It’s one thing to identify online drug sales, and another to do something about them.

“We do see a lot of accounts that are removed, they pop back up,” said Mackey.

He said that "whack-a-mole" phenomenon is largely due to inconsistencies in the approaches different platforms take in removing content.

“The bigger problem is that the platforms are not always coordinating with each other,” Mackey said.

That leads to a deeper question—whether social media companies really want to police online drug sales. While Snapchat has signed on to be a client, Mackey said pitches to other social media companies have gone nowhere.

“This is not something that's easy to sell. You know, going to a platform and saying, ‘Hey, you might have a drug problem, and we can help you find drug dealers on your platform,’” he said.

Despite those obstacles, Mackey said S-3 Research is in it for the “end game” of removing drug-selling content permanently online.

“Eventually, we hope that this part of the business goes away,” he said.

To Catch a Dealer Texas mom helps nab her son’s accused fentanyl dealer

Who are the dealers on the other end of a smartphone? And if they know that the fentanyl-laced pills they’re pushing are killing their clients, why keep selling them? One Austin-area mom got a real feel for that when her 19-year-old son died.

Becky Stewart said you would never have known her happy-go-lucky, funny son was really struggling on the inside.

“He had depression, anxiety, and instead of choosing to, you know, cope with those mental health issues in a positive way, Cameron made an extremely poor choice to buy a pill off Snapchat, and it contained a lethal dose of fentanyl,” Becky said.

After Cameron’s death, his mom wound up helping police arrest the man accused of selling her son the lethal pill.

“We kind of put two and two together and figured out who the guy was and found out he was at Cameron’s funeral and posted, ‘RIP we lost a good one,’” Stewart said. “The very next post was a handful of pills for sale. These dealers know that if their pill causes a death, those that are already addicted to it are going to know they have the good stuff-- ‘look, my stuff killed somebody, come and get it.’”

Becky said she asked a relative to send a friend request to who she believed was the dealer who sold to her son. Once he accepted, the family began taking screenshots of his Instagram posts. They said they forwarded them on to law enforcement.

According to court documents, one of those posts read “feds are on my a** but I’m still getting money and that’s no kizzy.”

“He doesn’t care if he gets caught. All he cares about is he’s still making money,” Becky said. “Because there’s always going to be a buyer right around the corner.”

According to a federal indictment, Cameron’s accused dealer, Juan Ignacio Soria Gamez, faces one count of distribution of fentanyl causing death, seven counts of distribution of fentanyl, and one count of possession with intent to distribute fentanyl. The causing death charge carries a maximum prison sentence of 20 years to life.

Defense attorney George Lobb said his client did not attend Cameron’s funeral because he was not in the U.S. at the time.

“The detective could have checked travel records to confirm this, but he did not,” Lobb said.

He called the police performance in the case “subpar and wrought with malfeasance” and claimed his client is a scapegoat.

“These families want justice and that does not have to involve putting another innocent man in prison,” Lobb said.

For Becky, the immense anger she feels inside also comes with an understanding that the mother of the accused also is grieving. Her son, just like Cameron, was a teenager.

“Nothing I do past this point is going to bring my son back,” Becky said. “So, no amount of rage or hate or any of that against him or towards him is going to change my situation. So, how can I turn that into a positive?”

Becky turned her grief into a passion for raising awareness about the dangers of fentanyl. She started the non-profit A Change for Cam in her son’s honor with the hope that no other families suffer such a devasting loss.

"It's a way to remember them" Moms find purpose in their pain

That commitment to change in the face of devastation can also be seen on nine acres in rural Montgomery County. The cadence of a cordless drill and the buzz of a power saw are more than a hobby or weekend project for Kenny Hall. What he builds is much more than wood and screws.

“It’s what it means when it’s put together,” Kenny said. “It’s a way to remember them. They’re not forgotten.”

Sarah Hall is Kenny’s wife and together they are on a mission to keep anyone from going through what they did with their son, Ethan Griffin.

“We’re here at the barn, feeding the horses, and we get a phone call that Ethan is unconscious at the house. We need to get home and that the cops are there,” Sarah said.

They rushed home to find their street blocked off by police and an ambulance.

“And I still remember the paramedic coming up and he knelt down in front of me and I was thinking, ‘No, no, no, no. You are not going to tell me this. This is not happening,’” Sarah said.

Fentanyl was found in Ethan’s system. The college student, aspiring musical artist and loving son was dead at 22.

“I just remember everything going black and fuzzy and complete numbness,” Sarah said. “It’s a bad dream. It’s just a really bad dream.”

With time, Sarah and three other grieving moms found purpose in their pain and started MCOPE, the Montgomery County Overdose Prevention Endeavor.

Focusing on education, remembrance, prevention and awareness, the group created The Texas Memorial Walkway. It’s a moving exhibit of the lives lost to overdose. At first, victims of all ages were dying from all types of drugs. Over the past year, Sarah noticed a change in the submissions— they’re nearly all fentanyl-related deaths— and the victims are getting younger.

Sarah arranges the photos for the poster-size tributes. Her husband, Kenny, builds the wooden bases— each one he constructs means another 10 lives lost.

“I would love to not have to build any more of these ever because of what they represent,” Kenny said. “This is to maybe stop somebody from going through what we had to go through and to let people know that it can happen to anybody.”

Kathy Posey, another MCOPE founder who lost her 23-year-old son, Josh, to an overdose, writes the personalized messages on each tribute and arranges the walkway when the exhibit travels. At a recent event hosted by Conroe Independent School District, the group displayed about 60 photos. At larger venues, the Texas Memorial Walkway has included 200 photos of those who passed.

“You look at their eyes and you can see they had hopes and dreams, you know. they didn’t plan to die,” Posey said. “We need to educate, and the thing is, I’ve seen a recent study that showed that a lot of kids, even though they’ve heard the word fentanyl, they don’t realize how dangerous it is.”

MCOPE’s mission is that when people walk through, reading their stories and seeing their faces, there is a connection.

“It’s powerful. It’s somber. It’s sometimes a little overwhelming, and a little in your face,” Sarah said. “And that’s the message we’re trying to send: it’s real. It’s really happening, you have got to be aware of what’s going on. We all thought this could never happen to our families, but it can. It can happen to you.”

Making it to the Capitol Fentanyl-related bills gain momentum

That message has reached the state capitol. From making it an emergency item this legislative session to hosting a One Pill Kills summit in Austin, Gov. Greg Abbott launched initiatives addressing the fentanyl crisis.

“Everyone in Texas has a role to play if we are going to effectively combat the spread of deadly fentanyl across our state,” Abbott said during the summit.

We requested an interview with Abbott and he declined.

At the capitol, the governor is backing a bipartisan bill, SB 654, authored by State Sen. Joan Huffman, R-Houston, that increases the penalty for manufacturing or delivering less than a gram of fentanyl to a third-degree felony. It also adds the offense to the engaging in organized criminal activity statute to allow for a second-degree felony charge. In death cases, SB 645 would allow prosecutors to file murder charges if a person “knowingly manufacturers or delivers” fentanyl and someone dies as a result. The bill also classifies fentanyl deaths as poisonings on an official death certificate.

“Prior to that, it was just called ‘accidental overdose,’” Huffman said. “A lot of times, the word accidental threw prosecutors off because they thought it was impossible to prove a murder or some type of intentional act.”

Huffman also is sponsoring SB 1319, which would require first responders to input overdose cases into a mapping program like this ODMap to track overdose hot spots and deploy resources to those areas.

In the Texas House, State Rep. Terry Wilson, R-Georgetown, has filed HB 3908. He’s pushing for mandatory fentanyl prevention and drug poisoning awareness education in schools starting in the sixth grade.

Several other bills would require teachers to be trained in administering Narcan. The bills would also equip public schools with the life-saving spray.

There’s a bipartisan effort to legalize fentanyl test strips in Texas, which are now considered drug paraphernalia. State Rep. Tom Oliverson, R-Cypress, is the author of HB 362, and he’s not just a lawmaker.

“I’m a board-certified anesthesiologist,” Oliverson said. “I use fentanyl every day on my patients.”

The legal, pharmaceutical fentanyl he uses is made in a real lab with quality controls. What exactly is in the stuff sold on the street is anyone’s guess.

“Right now, in Texas, there's no way to legally know what you're getting. That's what we're trying to change,” Oliverson said. “When we're dealing with something this potent and this potentially deadly, perhaps awareness is really the only chance of survival that you have.”

Everyone has a role to play in fighting the fentanyl crisis. There is no single solution. No one-size-fits-all. But as the death toll continues to climb, one thing is abundantly clear—doing nothing is not an option.

Resources If you or someone you know needs help

United States DEA Fentanyl Awareness: https://www.dea.gov/fentanylawareness

Find Treatment: https://findtreatment.gov/

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration: https://www.samhsa.gov/families

A Change for Cam: https://achangeforcam.org/

Montgomery County Overdose Prevention Endeavor: https://mcope.org/

National Helpline: 1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Know the code

Online drug selling is not always done out in the open but rather in code. The DEA created a reference guide to help give parents and caregivers a better sense of how emojis are often used.