The road to war between Japan and the United States began in the 1930s when differences over China drove the two nations apart. In 1931 Japan conquered Manchuria, which until then had been part of China. In 1937 Japan began a long and ultimately unsuccessful campaign to conquer the rest of China. Then in 1940, the Japanese government allied itself with Nazi Germany in the Axis Alliance, and, in the following year, occupied all of Indochina.

The United States, which had important political and economic interests in East Asia, was alarmed by these Japanese moves. The U.S. increased military and financial aid to China, embarked on a program of strengthening its military power in the Pacific, and cut off the shipment of oil and other raw materials to Japan.

Because Japan was poor in natural resources, its government viewed these steps, especially the embargo on oil, as a threat to the nation’s survival. Japan’s leaders responded by resolving to seize the resource-rich territories of Southeast Asia, even though that move would certainly result in war with the United States.

Understanding this, Japanese leadership developed a bold plan for a surprise attack. Approved just weeks earlier, the Japanese Imperial Navy Strike Group sailed toward Pearl Harbor, 73 years ago today.

The Pearl Harbor naval base was recognized by both the Japanese and the U.S. Navies as a potential target for hostile carrier air power. Its distance from Japan and shallow harbor, the certainty that Japan’s navy would have many other pressing needs for its aircraft carriers in the event of war, and a belief that intelligence would provide warning, persuaded senior U.S. officers the prospect of an attack on Pearl Harbor could be safely discounted.

During the interwar period, the Japanese had reached similar conclusions. But their pressing need for secure flanks during the planned offensive into Southeast Asia and the East Indies spurred the dynamic commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, to revisit the issue.

His staff found the assault was feasible, given the greater capabilities of newer aircraft types, modifications to aerial torpedoes, a high level of communications security, and a reasonable level of good luck. The key elements in Yamamoto’s plans were meticulous preparation, the element of surprise, and the use of aircraft carriers and naval aviation on an unprecedented scale. In the spring of 1941, Japanese carrier pilots began training in the special tactics called for by the Pearl Harbor attack plan.

In October 1941 the naval general staff gave final approval to Yamamoto’s plan. It centered around six heavy aircraft carriers accompanied by 24 supporting vessels. A separate group of submarines was to sink any American warships that escaped the Japanese carrier force.

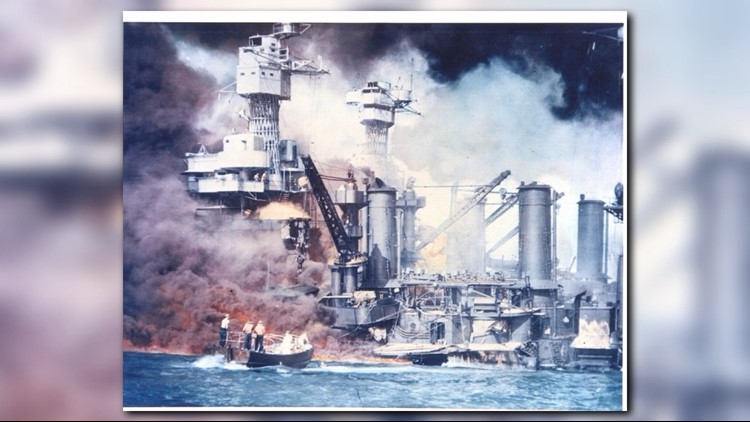

PHOTOS: The attack on Pearl Harbor

All six of Japan’s first-line aircraft carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku, and Zuikaku, were assigned to the mission. With more than 420 embarked planes, these ships constituted by far the most powerful carrier task force ever assembled. The Pearl Harbor Striking Force also included fast battleships, cruisers and destroyers, with tankers to fuel the ships during their passage across the Pacific.

An Advance Expeditionary Force of large submarines, five of them carrying midget submarines, was sent to scout around Hawaii, dispatch the midgets into Pearl Harbor to attack ships there, and torpedo American warships that might attempt to escape to sea.

Anticipating casualties from the pending attack, hospital facilities at Bako, Sama and Palau were told Nov. 26 to prepare to treat up to 1,000 casualties. The information came from intercepted Japanese messages that were not decoded and translated until after the war.

“Be prepared to supply 10 times the annual ‘battleship requirements’ of medical supplies for dressing of wounds and disinfection by Feb. 10, 1942,” one dispatch stated.

More ominous was a message from the day before: “Plans for exhaustive conscription of…and civilians are in hands of Central Authorities. In order to preserve security, however, they will be activated at a future time.”

The Japanese carrier striking force under the command of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, assembled in the remote anchorage of Tankan Bay in the Kurile Islands and departed in strictest secrecy for Hawaii on Nov. 26, 1941. If discovered, he was to abort the mission. The ships’ route crossed the North Pacific and avoided normal shipping lanes.

Upon their departure Prince Hiroyasu Fushimi sent this dispatch: “I pray for your long and lasting battle fortunes.”

The Imperial Navy carefully monitored all ships that might give away their plans. “Although there are indications of several ships operating in the Aleutians area, the ships in the Northern Pacific appear chiefly to be Russian ships.” The ships were identified as Uzbekistan and Azerbaldjan, both westbound from San Francisco.

As the Strike Group grew nearer, a dispatch ordered “all capital ships, destroyers, submarines of the South Sea Force and the Kukokawa Maru to maintain battle condition short wave silence,” starting at noon Nov. 29.

A Philippine merchant ship that arrived in Naha on Okinawa Nov. 30 had her radio sealed and departure delayed to “prevent their learning of our activities.”

A cryptic dispatch sent Dec. 2 was labeled top secret. “This order is effective at 1730 on 2 December. Climb NIITAKAYAMA 1208, repeat 1208.” Cryptologists examining this traffic after the war understood it to mean “Attack on 8 December.”

At dawn Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese task force had approached mostly undetected to a point slightly more than 200 miles north of Oahu. With a 19-hour time difference, it was Dec. 8 in Japan.