HOUSTON — Stephanie Shrimplin is on the hunt. She has 18 hours to find the father of a dead child.

Shrimplin isn’t a homicide detective, and the father isn’t suspected of foul play. She’s one of the more than 6,000 child protective services caseworkers statewide tasked with reviewing complaints, gathering interviews and making recommendations.

Shrimplin's case on this day involves 21-month-old Alan Villeda. The toddler was hit by a car and killed in the parking lot of an apartment complex the night before. Surveillance video shows his mom, Gissel Vazquez, holding her infant walking several feet ahead of the boy. She was charged with endangering a child.

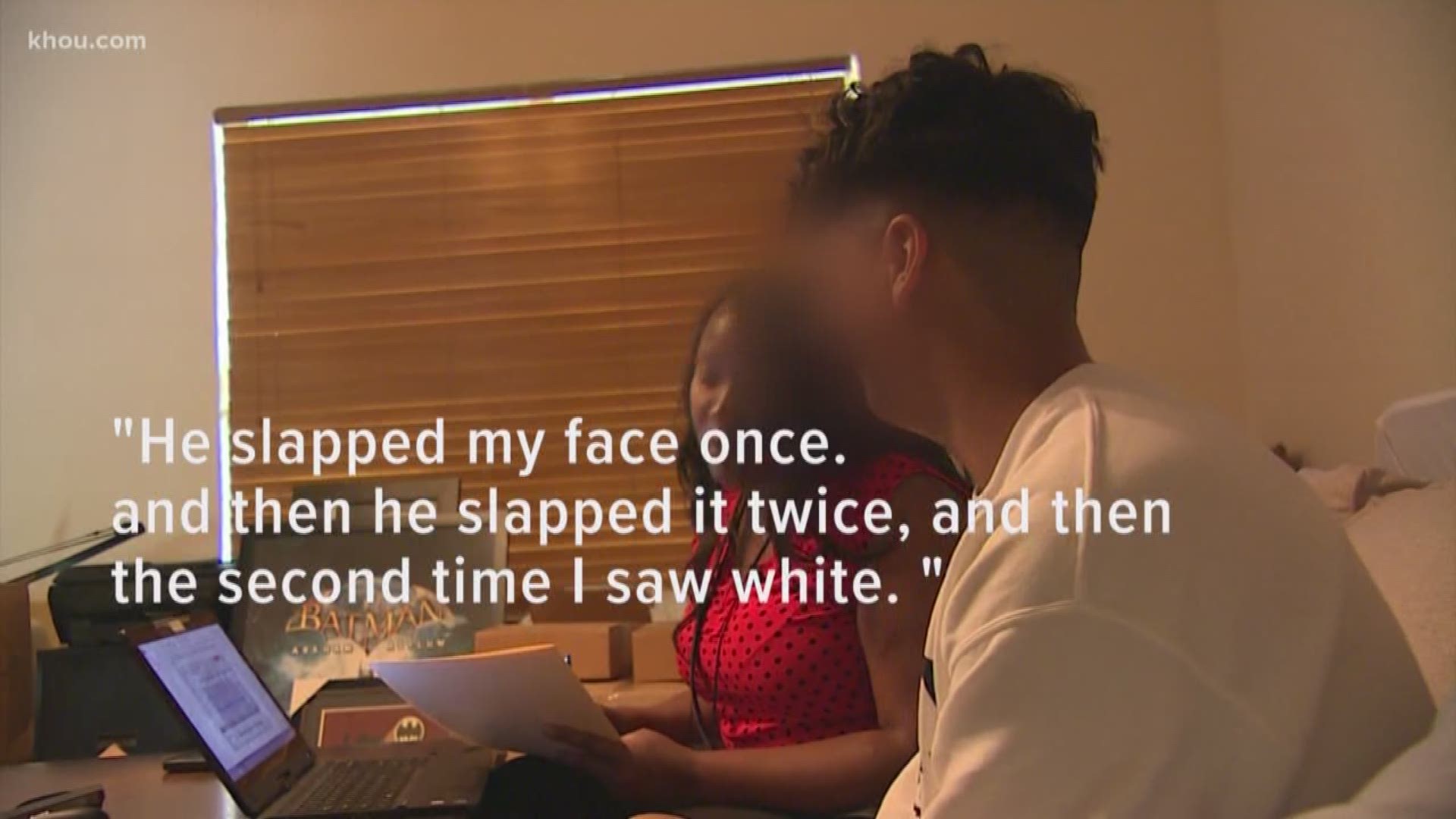

Shrimplin must interview the children's father to determine whether the surviving sibling Alan’s sister is safe. Her first attempt is at his apartment complex. But no one is home.

“I'm probably going to use the phone numbers I have to try to reach out to the family and see what's going on,” Shrimplin says.

KHOU 11 Investigates went out with two caseworkers to see what their average day is like. One of them investigates abuse allegations; the other, Shrimplin, is a fatality investigator.

“There's always something going on left and right in this city. It never stops,” she says.

A six-year veteran at CPS, she’s considered a seasoned employee; the average case worker has three years of experience, according to Texas Department of Family and Protective Services statistics.

"I got into the world of CPS mainly because of kids, to give them a voice, to give the kids that ultimate safety in their homes," Shrimplin said.

Fatality investigators must assess the safety of surviving siblings within 24 hours of a child’s death, and the clock is ticking.

Shrimplin makes some calls and learns the toddler's father is at a relative's house, which is a 30-minute drive away.

“You never know if you're going to be out here for an hour or six hours,” Shrimplin says.

She catches a break. The father and the surviving child are both there, but the father primarily speaks Spanish and requests a translator. So, there’s more waiting.

Finally, the assessment begins. Shrimplin introduces herself and dotes on the baby, Alan’s sister, that the father is holding.

“Look at you,” she says. “Look at all that hair.”

Before the interview can begin, she explains she has to take the baby into a private room to look for bruises and any other signs of abuse.

“I need to check her stomach, her legs and her bottom,” Shrimplin says.

The inspection takes less than five minutes. Shrimplin returns and the news is good. The baby is unharmed and healthy. She turns to interview the father.

“Have you ever been involved with CPS?” Shrimplin asks.

“No,” the man says.

She asks several questions about his background, childhood and his work life. Then the conversation shifts to Alan, his dead son.

“When Alan was living, how was your discipline with him?” Shrimplin asks.

“I just tell him no when he does things he is not supposed to do,” the father says.

He says he never hit Alan or gave him spankings.

Shrimplin then asks about how he learned of his son’s death. The man tells her that he was working out of town and got a phone call from a relative urging him to come home. He says he had not yet talked to the child’s mother about what happened.

Once the interview is over, the father grabs his phone and takes a moment to remember Alan. He breaks down as he watches a video of his son.

“Hang in there, and if there's anything you need just let me know,” Shrimplin tells him. “He's going to make me cry.”

As she wraps up her interview with the child's father, Vazquez arrives. She has just made bail. Before she left jail, she was questioned by Shrimplin’s colleague.

Typically, the two are together at the scene, but since they were split up, Shrimplin makes a call to her colleague to ensure they’re covering every angle, she says.

“If you miss something, or something is not getting communicated the right way, then you're not making the best decision for the family,” Shrimplin says.

She returns to the house to hear Vazquez’ side of the story herself. Vazquez tells Shrimplin she fainted and does not remember much. She also mentions another surveillance camera may tell a different story.

“Sometimes there are multiple stories and there are discrepancies in stories and you just try to do your best to find out who plays what role and then try to figure out what the truth is,” Shrimplin says.

Before she leaves, Shrimplin encourages the couple to join a grief support group at Bo’s Place.

“I do want to offer you my condolences. This case will be open but we are going to be here as a support to see what you need, what's working for you what's not working for you guys,” Shrimplin says.

CPS takes the information they gather and decides if a child is safe. If they are not, several options are available, including placement with family members or getting the court involved. The baby will stay with her parents for now. But Shrimplin’s work has just begun. She has to return to the office and file her official report.

It's a job, Shrimplin says, that’s tested her patience during her six years as a caseworker.

“There's been a couple of times I've been burned out. Not in the fatality unit yet, but in regular investigations there were times that I lacked motivation. It comes and goes,” Shrimplin says.

Burnout is a documented reality at CPS. More than one-fifth of caseworkers quit or are terminated every year, according to DFPS statistics.

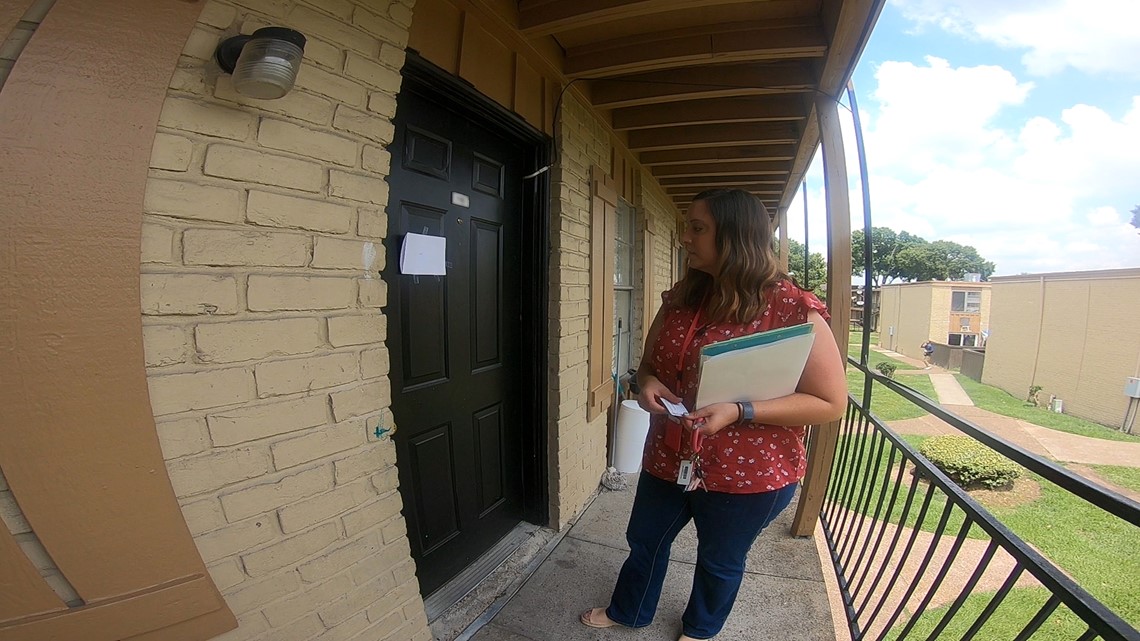

Caseworker Dorothy Inyangala is not one of them. She started working for CPS four years ago.

Around mid-morning on another day, Inyangala gets on the road. She said it is where she spends most of her time, clocking 150 to 200 miles a day.

Today will be the same. She is gathering information on two reports of alleged abuse. Her first stop involves three teenagers.

“A call came in saying the father in this home has been using inappropriate discipline, and hit the child to the point that he blacked out,” Inyangala said.

When she arrives, she reviews the report and prepares to interview everyone involved. Inyangala has 72 hours to gather the information. She greets them at the door and gets to work.

She tells the teens' grandmother that she will be doing the interviews in private. KHOU agreed not to name the occupants to protect their identities.

Inyangala begins the interview with a brief introduction. It’s a spiel she says multiple times a day. DFPS estimates an average caseworkers takes on about 18 cases at a time.

“Do you know what child protective services is? What we do is go to homes and schools and talk to kids and make sure kids are safe, and today is your turn because someone is worried about you,” Inyangala says.

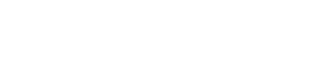

One of the teens tells her about a time he said his dad knocked him out.

“(Dad) spit in my face. He slapped my face once, then he slapped my face again, and then I saw white,” the teen says.

“You saw white? Like, what do you mean?” Inyangala asks.

“You know, when you get hit, like when you play football and you hit the ground,” the teen says.

“You lost consciousness,” Inyangala asks.

“Like for a split second, yeah,” the teen says.

“How long has this been going on? The whooping? The slapping?” Inyangala asks.

“My whole life,” the teen says.

Inyangala follows a similar line of questioning with the two other teens before she interviews their grandmother.

“The father, have you seen him discipline these children,” Inyangala asks.

“Yes. I’ve seen him twice when I came to see my daughter,” the grandmother says.

“He hits them in the face,” Inyangala says.

“I saw the dad hit the two boys in the face. One was like five years ago and the other was like two years ago,” the grandmother says.

“How come you don’t call the police when this happens,” Inyangala asks.

“I thought it was not my place, but I should have called,” the grandmother says. She later adds that the teens’ mother already contact the police about the allegations.

Inyangala records the conversations on her laptop and takes detailed notes. She takes a short tour of the house before she leaves. She checks the bedrooms and asks where the children sleep. Her last stop is the kitchen. She opens the refrigerator and takes a glance. It is full. Before she leaves, she makes sure the household knows who to call if they feel like they are in danger.

The teens didn’t have any visible signs of abuse on their bodies, Inyangala notes after she leaves, and prior abuse is difficult to prove.

“The problem is delayed outcry. The police are going to get involved, of course. They already came and made a report. So, they will investigate and make a decision on whether to arrest (the dad) or not,” Inyangala says.

She gets inside her car, calls her supervisor with an update and checks her email before hitting the road.

Her next stop 40 miles away, the Galveston County Jail.

“The allegations came in saying that the mother is not capable of taking care of the child. Mom was on drugs, or is on drugs, and the father is in jail for possession of a controlled substance,” Inyangala says.

She’s in and out in a matter of minutes. Her brief visit is mostly centered around telling the father that his newborn’s mother will not keep the child, who was born premature and is still in the hospital. Their baby will be placed with the mother’s parents, but the father’s parents will also be involved, she reassures him.

Both sets of grandparents passed background checks and have never been the subject of a CPS investigation, Inyangala says.

”These (grand)parents are appropriate,” she says. “They’ve been involved and have been reporting abuse or allegations of abuse. They have been calling and doing what they need to do to make sure that child is safe.”

The Galveston County Jail is Inyangala’s final stop for the day. She says having two cases is rare. The summer, she says, has not been slow.

It’s an indication of something dark, Inyangala says.

“That there is abuse.”