SAN FRANCISCO — On Sept. 8, an ungainly, 2,000-foot-long contraption will steam under the Golden Gate Bridge in what’s either a brilliant quest or a fool's errand.

Dubbed the Ocean Cleanup Project, this giant sea sieve consists of pipes that float at the surface of the water with netting below, corralling trash in the center of a U-shaped design.

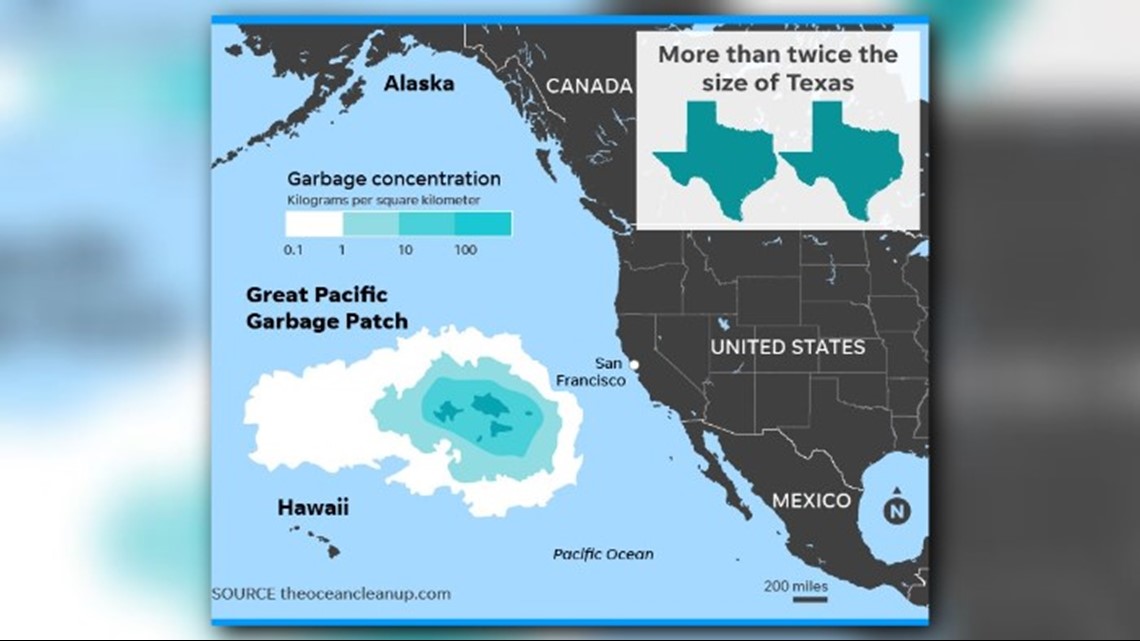

The purpose of this bizarre gizmo is as laudable as it is head-scratching: to collect millions of tons of garbage from what's known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which can harm and even kill whales, dolphins, seals, fish and turtles that consume it or become entangled in it, according to researchers at Britain's University of Plymouth.

The project is the expensive, untried brainchild of a 23-year-old Dutch college dropout named Boyan Slat, who was so disgusted by the plastic waste he encountered diving off Greece as a teen that he has devoted his life to cleaning up the mess.

Along with detractors who want to prioritize halting the flow of plastics into the ocean, the Dutch nonprofit gathered support from several foundations and philanthropists, including billionaire Salesforce founder Marc Benioff. In 2017, the Ocean Cleanup Project received $5.9 million in donations and reported reserves from donations in previous years of $17 million.

How it works

The Ocean Cleanup Project's passive system involves a floating series of connected pipes the length of five football fields that float at the surface of the ocean. Each closed pipe is 4 feet in diameter. Below these hang a 9-foot net skirt.

The system moves more slowly than the water, allowing the currents and waves to push trash into its center to collect it. Floating particles are captured by the net while the push of water against the net propels fish and other marine life under and beyond.

The system is fitted with solar-powered lights and anti-collision systems to keep any stray ships from running into it, along with cameras, sensors and satellites that allow it to communicate with its creators.

For the most part the system will operate on its own, though a few engineers will remain on a nearby ship to observe. Periodically a garbage ship will be sent out to scoop up the collected trash and transport it to shore, where it will be recycled.

Misguided focus

Marine biologists who study the problem say at this point things are so bad that it’s worth a shot.

“I applaud the efforts to remove plastics – clearly any piece of debris cleared from the ocean is helpful,” said Rolf Halden, a professor of environmental health engineering at Arizona State University.

But he added a caveat, namely that there’s not much point to cleaning up the mess unless we also stop the tons of plastic entering the oceans each day. “If you allow the doors to be open during a sand storm while you’re vacuuming, you won’t get very far,” Halden said.

And that gets at the heart of some of the criticism.

Stopping plastics from making their way into the oceans "should be the focus of 95 percent of our current effort, with the remaining 5 percent on clean up," said Richard Thompson, who heads the International Marine Litter Research Unit at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom.

"If we consider cleanup to be a center stage solution, then we accept it is OK to contaminate the oceans and that our children and our children’s children will continue to clean up the mess," he said.

Another concern is that the project only targets plastic pollution floating at the top of the ocean, although researchers have found microplastics from the waves all the way down to the sea floor.

“They’re not all buoyant. Some sink, some remain floating at different levels based on their density and the water pressure,” said Charles Rolsky, a Ph.D. researcher who studies ocean plastic pollution at Arizona State University.

There’s also the possibility that the contraption might break up in storms and simply make more plastic trash.

“The ocean is strong and powerful and likes to rip things up,” said Miriam Goldstein, director of ocean policy at the Center for American Progress and an oceanographer who together with physical oceanographer Kim Martini has been publishing critiques of the project.

The foundation – which openly refers to itself as a "moon shot project" – responds that cleanups are an important part of the story.

"The current plastic pollution will not go away by itself," spokesman Rick van Holst Pellekaan told USA TODAY in an email.

To deal with the baseline problem, he said the project is considering spinoff systems for coastal areas and rivers that would intercept plastic before it reaches the ocean.

There's a lot to be stopped. As much as 9.5 million tons of trash is deposited into the ocean each year, according to a report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Plastic is different than other trash because it never decomposes. While it breaks down into smaller and smaller parts called microplastics, they never become bioavailable, meaning they can never provide nourishment to marine life.

The biggest sources today are countries that have rapidly developing consumer economies but whose waste management practices haven’t caught up, often in Asia.

“They simply don’t have the systems in place to deal with this nondegradable material,” Goldstein said.

Discovering the Patch

First described in 1988, ocean-borne trash patches such as the Pacific one consist of a huge concentration of garbage, mostly made up of plastics. Due to circulating ocean currents called gyres (something like slow-moving whirlpools) they accumulate floating trash in areas hundreds of miles across. There are five gyres worldwide, according to the National Ocean Service.

About 70 percent of the litter in these patches is made up of plastic, according to a British study published last year, with close to 50 percent made up of discarded fishing nets, a study published by the Ocean Cleanup Project found earlier this year.

It was cleaning up these convergence zones that obsessed Slat after his high school diving experience. He eventually presented a TED talk on some of his ideas after he graduated from high school in 2013.

That talk went viral, a crowdfunding project to raise money to implement a cleanup began, and Slat ended up dropping out of the aerospace engineering department at Delft University to focus on the cleanup.

Fast forward five years, and a team of international engineers and scientists who have been working to build the cleanup system across the bay from San Francisco are weeks away from launch.

The plan

The project's first cleanup system is scheduled to be towed out to a spot 240 nautical miles off the U.S. coast on Sept. 8, from a dock in Alameda, California, where it's being built. It will spend between 40 and 60 days there for real-world testing.

The event will be live-streamed online, and the nonprofit is also welcoming supporters to come see it in person as it sets off on its maiden voyage.

If it performs well, the system will then be towed out a further 960 miles to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch between California and Hawaii.

The goal is to deploy 60 such systems by 2020, which the group believes will clean up 50 percent of the garbage in the garbage patch in five years time.

While the scientists who study ocean plastic pollution aren't convinced this will fix the problem, it might help bring the problem more into the public eye. In Rolskly's opinion, there's just one good thing about plastic pollution – it’s one of the few forms of pollution you can see with the naked eye, which may in the end be what helps end it.

“It’s really repellant,” he said. “It triggers the right emotions to get the political will to implement change.”